In our latest Digital Lighthouse episode, Zoe Cunningham is joined by Will Dixon, Professor of Digital Epidemiology at the University of Manchester.

Will discusses how digital health data sources create exciting opportunities, like using de-identified electronic health records to analyse large populations for medication safety and COVID risk factors during the pandemic. He also explores the risks and challenges of managing data from patients and the public via smartphones and wearable devices to gain a clearer understanding of health.

Don’t miss his ‘Cloudy with a Chance of Pain’ research, where Will investigated the link between weather and arthritis pain using smartphones to collect data from over 13,000 participants. He is optimistic that integrating patient-generated data into the healthcare system will improve clinical outcomes and address vital health inquiries. Learn more by listening to the podcast or reading the full transcript below.

Digital Lighthouse is our industry expert mini-series on Softwire Techtalks; bringing you industry insights, opinions and news impacting the tech industry, from the people working within it. Follow us to never miss an episode on SoundCloud now: See all Digital Lighthouse episodes on SoundCloud

***

Transcript

Zoe Cunningham: Hello, and welcome to the Digital Lighthouse. I’m Zoe Cunningham. On the Digital Lighthouse, we get inspiration from tech leaders to help us to shine a light through turbulent times. We believe that if you have a lighthouse, you can harness the power of the storm. Today, I am super excited to welcome Will Dixon, who is Professor of Digital Epidemiology at the University of Manchester. I think, Will, that is the most exciting title that anyone on the podcast has ever had. Welcome to the Digital Lighthouse. Tell us what it means to be a professor of digital epidemiology.

Will Dixon: Thank you, Zoe. Thanks for the invitation to join you. I think prior to the pandemic, I’d have to explain to people what epidemiology is, but people have heard of epidemiology and epidemiologists over the last couple of years. Epidemiology is the study of diseases in populations. We’re interested in finding out the causes, the consequences of living with disease by studying data across whole populations.

The digital part of my title is that I’m interested in using digital health data sources to study epidemiology. That might be the use of electronic health records. If you go and see your GP, or if you go and see me, I’m a consultant rheumatologist as well at Salford Royal, then we’ll enter information into electronic health records, primarily to help guide your clinical care. If we de-identify all of that data and manage the data securely, then we can analyze data across large populations of people, for example, to look at the safety of medications or to understand the risk factors for who might develop COVID that led to the guidance of who should shield during the pandemic.

Electronic health records are one data source, but I think one of the really exciting opportunities in the last 5 to 10 years, and that will only get bigger, is the opportunity to collect data directly from patients and the public themselves using the devices that we all carry around with us via smartphones, via wearable devices. That can cover so much richer and clearer picture about health that will complement rather than replace what we could already know from electronic health records and other data sources.

Zoe: Tell me a bit about where we’ve come from then, like how we’ve got to this point. How’s it worked in the past?

Will: I can answer that through the story of the center that I directed in Manchester. I’m the director for the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis. This is funded by the national charity, Versus Arthritis. They’re focused on musculoskeletal disease. Actually, we’ve been doing arthritis epidemiology in Manchester since the 1950s. When the center began in 1954, one of the first projects that they did was looking at the relationship between coal mining and rheumatism. You can imagine working underground, digging away at coal fields in cramped conditions. They were asked by the National Coal Board whether that might lead to musculoskeletal problems, that it leads to osteoarthritis of the knee, that it caused back problems.

To do that research, the team in the 1950s would drive out to the coal fields. They would do X-rays of minors, they would ask questions, and then they would record the responses to those questions on punch cards. They created holes in these small pieces of cards, then thread a stick through the holes and shape the stick. Then the number of cards that fell to the floor would help them count how many people did or didn’t have a certain response.

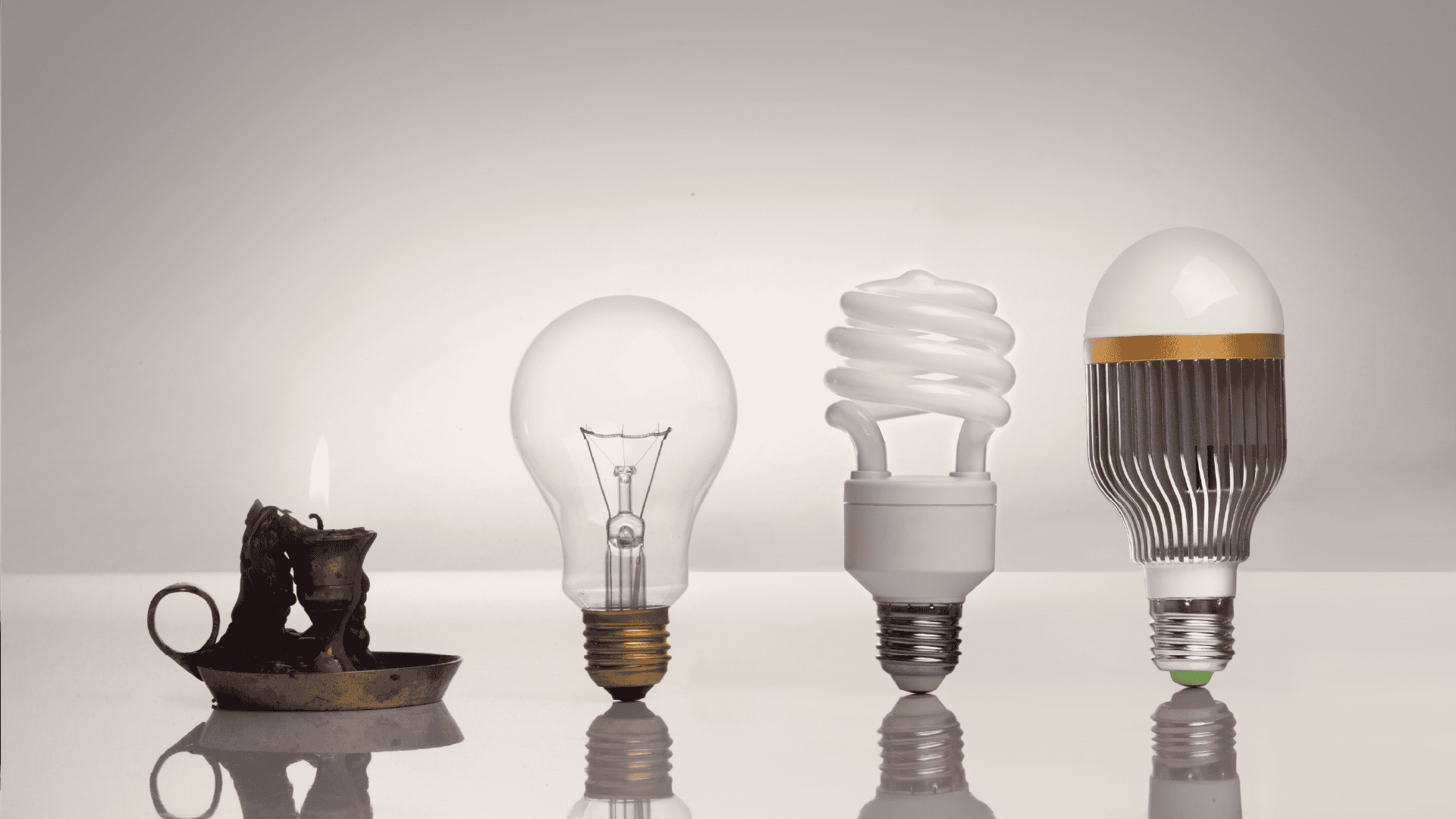

You can see that the concept of epidemiology is unchanged. We’re trying to measure how frequently people have diseases and what are the risk factors for those diseases. Mining and rheumatism was one example of that, but the methodology for doing that, the way in which we can collect data has really changed over the years. From going out doing surveys, that have advanced over the years to sending out postal questionnaires, we’d receive that back and we transcribe that into a database. Then it moved into national registers and cohorts where we collect information from clinical colleagues and again, we’d enter that into a database. Now, moving into the reuse of routinely collected data, which is held digitally, and now as I’ve just explained, advancing into collecting data directly from patients themselves using their own technology.

Zoe: I think there are two different things that are going on that are going to change things. There’s this increase in our ability to collect data so we can collect more data more quickly and more conveniently, which like you say, even postal data is an improvement over physically having to travel somewhere. Then being able to even connect to your device, which I’d love to talk about as well, like what kind of applications there are there? Also, then the fact that I suppose there was medical data collection more generally in the 1950s, was there, or is that something that’s really ramped up recently?

Will: Well, it’s interesting that we’re about to– it’s next week, we celebrate the 75th anniversary of the NHS. Our center for epidemiology began only a few years after the launch of the NHS, but both of which were in Greater Manchester. There wasn’t so much routinely collected information then, and it hasn’t always been accessible for research. Although, I talked about this great opportunity from health records.

Historically, health records were a series of paper documents that were held together in a paper wallet that was filed in your GP surgery. If you want to analyze it across thousands of people, you’d have to sit down and open every little wallet, read through it, and collate that information yourself, but given that it’s now digital data, that’s much easier to do. You’re right, that the availability of data, it’s always been there. How accessible is it for research? Is the quality good enough? What is it that we’re collecting? Is that just in one part of the health system and not another? That has continued to evolve through time.

Zoe: Can you give us some examples of the kind of data of research that’s going on right now, then?

Will: Before I do that, let me perhaps introduce why smartphone-based health research is exciting. We’ve talked about being able to collect data directly from patients, but it’s a bit more than that. The first thing is that we can collect data that previously were hard to collect. We can collect the same thing, so kind of a paper-based questionnaire you can put onto a digital screen. You can also do much more than that because the touchscreen is interactive.

The second thing is that you can pull information from smartphones, other technology. The phone’s a bit like a Swiss army knife. It’s not just a touch screen, but it also has a camera and microphone, an accelerometer, gyroscope, GPS, and more kit within it, which if we think creatively, we might be able to also use for health research. I’ll come on to an example of how we can do that. Secondly, because in theory, you can track things regularly through time, you can integrate this data collection into people’s lives. Rather than having information as a snapshot from when you happen to go to the GP once every six months, you can collect information on a day-to-day basis, so it can have a richer time series of data.

The third thing is that the uptake of consumer technology has been exponential, and now 9 in 10 people own a smartphone. Obviously, it’s not everyone, we need to be sensitive to that and understand when our results can be generalized to everybody, but 9 in 10 is not bad either. We have the potential to reach most of the population through this method. Then also, we can change the way in which we do study design.

We can look at differences within an individual rather than just comparing between people in a population. We can analyze in different ways because the data is vast, we can start to use machine learning and AI. Lastly, you can also present information, facts to people to keep them engaged or even to do interventions. Health intervention that might be, say, digital coaching through a smart screen.

All of those opportunities together can potentially transform how we do epidemiology. I said I went off on a tangent to tell you that because you’d asked me about a specific case study. One example that we ran a few years ago was a study that was investigating the age-old belief that the weather can affect pain in people with arthritis. It’s something that a lot of people have heard of, you might have heard somebody say, “I can tell it’s going to rain because I can feel it in my head.” It’s a well-known old wives’ tale that there’s a relationship between the weather and the symptoms.

Previous to our study, nobody really answered this question, what was it within the weather that affected this relationship? Making use of all of those advantages that I just spoke about, we asked people to track their symptoms every day so that allowed us to track the symptoms through different seasons, allowing you to be exposed to different weather data. We can see how things changed in response to the weather. We use the GPS within the smartphone to then link to the local weather data. We built up a dataset of over 13,000 people, we track their symptoms across many seasons over 5 million data points. That allowed us to examine whether the weather influenced pain if you’ve arthritis, a study called Cloudy with a Chance of Pain.

We found that painful days were associated with high humidity and low pressure, which some patients described, particularly the forecasting aspect, the fact that people believe that they can tell what the weather’s going to be. There would have to be something in the weather today that is causing your symptoms that also relates to the weather to come. That’s pressure. I think you then get a change in pressure that then changes how the weather over the next few days happens.

Zoe: Fantastic. I think that as human beings, we obviously have all this sophisticated sensing data already, but also we have the ability to come up with links that aren’t there, right? [chuckles] Actually, when you can tell the difference, that’s when you can start to use it and improve people’s lives.

Will: I think that’s right. The Cloudy with a Chance of Pain was doing what we all try and do every day. The science in our everyday lives is that if you have a bad day, you think, “Well, why is it I’m feeling like this?” What you do mentally, but without hard data to back it up, you try and compare a bad day to comparing to a good day and what was it that happened on your bad day compared to what it was that happened on a good day. That’s exactly the analysis method that we used in Cloudy with a Chance of Pain. You could only do that because you’re measuring how things have changed on a day-to-day basis within an individual. We can make that with an in-person comparison.

Zoe: What are the challenges then for you [chuckles] in terms of we’ve got all this amazing data, amazing technology? What are the challenges?

Will: There are endless challenges actually. I think the hype of using smart phones for health research has been around for a long time. You can find articles that say, “Mobile phones will deliver data bounty dating back 10 years.” Yet if you look at how many studies have actually successfully run from beginning to end and created the results that they intended to, there were only a small number of them. Some of them really impactful and really important, like the COVID ZOE app, that was outstanding. Lots of people around the country participated in that. In total, around 4 million people.

An interesting statistic about this is that the NHS had set a target of wanting to have 100,000 people contributing to health research studies in 2019. Then, during the pandemic, the COVID ZOE Study recruited one million people in one day. [chuckles] One study recruited 10 times the national target for recruitment over the year. Then ultimately, they recruited 4 million people. Made it possible because of the opportunities that I’ve described, the number of people that have smartphones.

One of the challenges, well, if you are trying to collect data from patients and the public, particularly if you’re trying to do that regularly through time, people have to be motivated to take part. They have to understand what is it that you’re trying to do. They have to want to contribute. Perhaps there even needs to be something in it for them for doing their symptom tracking side or helping them learn about what are those triggers for the flares in their disease. You have to partner with patients and the public in the right way so that you are answering questions that matter to them. If you are trying to get them to use technology, it has to be designed in the right way. It has to be easy and simple to use. It has to get the right data out. That data has to be valid. It has to measure what you think it’s measuring. It needs to be repeatable through time without it drifting and changing.

You have to understand how the data will flow, to be able to describe that to participants. You have to take their consent to participate by saying that now it’ll be collected within this app, in the following way, and then it will flow to this place, and these people will have access to it. All of the information governance around it is challenging how you then analyze this time series data. Instead of just a change from baseline to six months, your pain score is improved by six points from eight to two. Actually, we’ve got another 180 data points in between. Then how do you describe that easily? What’s the statistics that you use to measure that change in pain?

There’s all sorts of challenges, and actually, you have to solve all of them to get from beginning to end. A lot of studies struggle somewhere along the way. I’m actually recording the podcast from Softwire in Manchester today because we are indeed trying to develop a new way of collecting side effects from patients, in a way that’s simple and easy to do, in a way that people would want to do, in a way that gives us valid coded structured information at the end. Going from a story of what happened with your side effects to a code that somebody got nausea or somebody had diarrhea or somebody had a severe rash.

That’s quite a challenge technically, but it has to be done in a way that patients probably can engage with and understand and use easily. We’ve got 10 patients coming in to talk through the preliminary design so that we can then get to a position that it suits my needs as a researcher, but also patients of the public would engage with.

Zoe: It’s really interesting actually hearing about the challenges after the example about the ZOE app. People did see how it was relevant and a large number of people saw how it was immediately relevant for them [chuckles]. This was suddenly a disease that we were all at risk of, and I think there was incredible amount of motivation, wasn’t there, for people to get involved and report accurately and support the initiative.

Will: Yes, that’s absolutely right, and it was affecting everyone in the country in different ways. Not everyone had COVID at the same time, but everyone was aware that they might, and everyone wanted to contribute to a better understanding of this thing that we didn’t initially understand. We’re not going to often be recruiting 4 million people to a health research study, but it stands out as a really incredible example of what the power of such research is and showing that you can recruit a scale showing that you can generate clinically important information from it.

For example, from that COVID ZOE Study, when it began, we didn’t really know what the cardinal symptoms of COVID infection were. Through the symptom reporting from those 4 million participants, we came to understand that a loss of sense of smell was a key feature. It’s hard to remember back, but at the beginning, we didn’t know that. It was only because we collected the information from all of those participants that that changed the guidance and the definitions. Then it was, well, if you’ve got a loss of sense of smell, then you should definitely go and get a COVID test.

Zoe: Yes, and I think we all knew it was a bit like a cold [chuckles], so coughing and sneezing, but actually realizing that the coughing was important, the sneezing wasn’t important. Then, like you say, these strange symptoms like loss of taste or food tasting strange, which I guess is linked to the smell, right? That’s where we’re at now. What are you hopeful that we’re going to be able to do in the future?

Will: Well, I touched on earlier that I’m also a consultant rheumatologist, so I look after people with arthritis in my clinic at Salford Royal Hospital. I think what may well happen is that although it’s difficult, I think we’ll start to integrate patient-generated data into the NHS but be thinking also about how we might use that data for health research. If we do that successfully, we will have a sustainable stream of data collected for purposes that patients and the public understand.

We collect information once but can reuse it for multiple things. Let me tell you about another study that we’ve got running at the moment. This is called, REMORA, which stands for The REmote MOnitoring of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatoid arthritis is one of the most common inflammatory joint problems. You get pain, swelling, and stiffness in your joints because of inflammation in the joints that affects just under 1% of the population.

This is a disease that flares through time, so sometimes people can be well and other days, their symptoms will get worse, they’ll get more stiffness in the morning, more pain, more difficulty performing daily tasks. The way that I as a rheumatologist assess and help manage people’s conditions is that I’ll see them in clinic, say once every six months. My opening question to my patients is, “How have you been since I last saw you?” Really, that’s possibly one of the hardest questions to answer [chuckles]. How can you possibly describe in a minute the symptoms that have gone up and down, many different symptoms that you have that impact on your daily life, how that’s affecting all sorts of aspects of your life?

In REMORA, what we’ve done is we’ve designed with patients and the public, a smartphone app and a linked system whereby people can track their symptoms, a bit like in Cloudy with a Chance of Pain, how bad is your pain today on a score of 1 to 10, range of other symptoms collected. Then the data flow into a central location within the NHS. Then we have a graph of how somebody’s been, that’s available and integrated into the electronic health records. Without me needing to log on to a separate system as a doctor, I can immediately see a graph of how somebody’s been since they were last seen.

That, in theory, allows us to have a clearer picture of how somebody’s been, make better-informed decisions, and therefore, lead to better clinical outcomes. We’re about to go into a randomized trial across two regions of the country to test whether this does indeed lead to better clinical outcomes. Using smartphones to support clinical care, but then if you’ve got these track daily symptoms in patients, then you can layer on top of it just consent to reshare that data.

If we took consent to do the GPS, then you can reproduce Cloudy with a Chance of Pain without having to set up a completely separate research study, so you have this opportunity to integrate the two things. I think that’s where it will get really exciting. We’ll learn a lot about causes of disease, learn about the lifestyle factors, how changing those can influence people’s disease. Everyone wants to know, what can you do differently? If I were to change my physical activity, if I were to change how I sleep, what about the diet? Now, if you’re able to track those things alongside tracking symptoms, then it opens up answers to all of these questions that we know are top priority for patients and for clinicians and researchers.

Interestingly, there have been exercises by an organization called the James Lind Alliance that bring together those three groups of people, so patients and doctors, and researchers and so what are the 10 most important questions that you have that aren’t yet answered? They’ve done it in around 200 different health conditions. If you take any one of those 200 groups and you read through the list of 10 things, there are almost invariably things that haven’t been answered but could be answered if only you could collect directly to the patients in public regularly through time.

Zoe: And accurately.

Will: And accurately, yes

Zoe: I think you’re quite right that this is so exciting that actually linking up this, why would someone engage in this study and what motivates them to, not just start a program, but keep with a program and keep collecting the data? That is an important piece of the puzzle. You can’t just say, “We need data,” because even the most well-meaning people, it’s very hard to stay motivated if you don’t really understand why you’re doing it. Then at the same time, once you have that data, there’s the uses we know about now and uses we will find in the future as well, so super exciting.

Will: Yes, and I think a really important part of this life cycle of a study, not just what question we’re trying to answer or what data do we want to collect about it, but right through to the end when you get the research results, we have the potential through this technology to provide that feedback back to participants. You’ve kindly contributed to this study. Here are the results. Here’s what we’re finding. The ZOE study did an exemplary job of this, and I hope it will be ultimately transforming how everyone has to do this in the future, that you need to have a dialog with your participants to tell them what you’re finding.

Prior to that, there was a whole program around recognizing the need to not just have people as participants, but actually to feed the results back to them. We didn’t do a very good job of that as a research community. I think the COVID ZOE Study is an excellent example of where they did that with regular webinars. If we want people to be inputting data regularly, there needs to be a shift in power and a change in the nature of the relationship between the researchers and the public.

Zoe: Yes, absolutely. Which just goes to show that, yes, technology advances, and that’s important, but actually, it’s our understanding and models that we have also advance and that’s an important corollary alongside it.

Will: I think technology has to support what it is that we should be doing anyway. We should be answering research questions that matter to patients. It’s even more important we do it if we want people to engage, but technology is only there to facilitate that. We know that there are these things that we can only answer if we track them through time. How does diet influence your symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease?

We can only do that if we can track symptoms through time, and actually, technology provides an opportunity to do that. The feedback through the screen isn’t there, just because we can do it. It’s a fundamental part of what we should be doing anyway, but now we have the opportunity to do it better.

Zoe: Well, thank you so much, Will, for coming on and sharing all of this insight and enlightenment with us today.

Will: No, you’re very welcome. It’s been a pleasure.