Is the hype around Generative AI a chance to rethink tech strategy?

The seismic impact of Generative AI (GenAI) is a timely reminder why CTOs need a nimble tech strategy that moves with the times. Tech adoption can’t continue as a large, expensive infrequent activity – it must be done quickly and with an amount of risk proportionate to the potential gain. It must become business as usual.

This approach enables you to keep pace with accelerating technological change while extracting their transformational qualities, while — crucially — reducing expensive long-winded missteps.

But how do you get there? In this article, we look at:

- The ever-shortening lifespan of technology

- Key lessons from the shift to the Cloud

- Three strategic changes to move tech adoption to BAU

The ever-shortening lifespan of technology

The hype around GenAI is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it has started conversations about how and when organisations can adopt this particular new technology. On the other hand, such hype risks becoming yet another distraction from a broader and more pervasive issue: how quickly organisations can adopt new technologies more generally.

It is safe to assume that GenAI is not going to be the last highly disruptive technology CTOs need to worry about. Arguably it is not the first either; although it has caught the imagination of the public (and business leaders) in a way cloud computing, say, did not.

Disrupt yourself before someone does it to you

A strongly related industry theme is the ever-shortening “shelf life” of technologies. Twenty or thirty years ago, organisations would expect large technology investments to have relatively long lifetimes. In fact, some organisations are still running on technology from this era (mainframes, enterprise databases, et cetera).

The challenge now is that technologies are being superseded at an alarming rate. In essence, this means not only do organisations need to adopt technology far more quickly, but also once adopted that technology will likely become out of date even sooner.

One useful definition of technology that has passed its “business shelf life” is where continued use of that technology opens an opportunity for a competitor. For example, can a newer technology allow a competitor to create a better, more compelling business offering for less money? New technologies can also lower the barrier to new entrants to a market or create wholly new business opportunities.

The best CTOs are always looking for new technology that will give them that edge (and hopefully save them money). One CTO I worked with used to ask: “Tell me how you would use technology to put me out of business” – he was constantly on the lookout for opportunities and threats. As the saying goes, disrupt yourself before someone does it to you.

Clearly there are other reasons for seeing technology as out of date, such as being out of support, being unable to find the required skills, or being unable to easily apply modern ways of working. My experience is that these usually get spotted some time after the “business shelf life” has expired.

Key lessons from the shift to the Cloud

So how best to react to this complex situation? For GenAI, one path would be to find a short-term way to shoehorn this technology into an organisation’s technology landscape. This might well make the CEO or the shareholders happy, at least until the next disruption arrives.

Arguably many organisations did this with cloud – they did a “lift and shift” of existing architectures and infrastructure design into the cloud, effectively treating it as just another hosting provider.

Those same organisations are now struggling with low ROI as they find themselves unable to take true advantage of things like elasticity, self-service and better resource measurement.

A similar risk exists with GenAI. For example, by treating it as a simple equivalent to an existing capability such as a chatbot or a human customer service agent. This isn’t taking proper advantage of this transformative technology, but rather just seeing it as a new way to cut costs – much the same as some organisations saw the cloud.

The danger here is of course that in a few years’ time the same results are likely: low ROI on a potentially large technology outlay.

This pattern of large technology investments that fail to deliver on their promises is something many people working in the technology industry will recognise. In part, it repeats because many organisations still treat the adoption of new technology as “one-off”, once-a-decade event.

Instead, adoption of new technology must become business as usual. The pace of technological change is accelerating, and technology is the key enabler for many organisations. Technology adoption cannot remain as a large expensive highly infrequent activity but should become something organisations can do quickly and with an amount of risk proportionate to the potential gain.

Below I outline just some of the broader strategic changes organisations need to make to move to a BAU situation for technology adoption.

This is clearly not an exhaustive list, for example there are also changes needed to delivery capability, project and programme management, technology governance, PMO, and so on. But it’s a good starter for ten.

Three strategic changes to move tech adoption to BAU

1. Make smaller investments more often

Any given technology will be superseded by a better and cheaper alternative, often much more quickly than we expect.

In past decades, making a large strategic technology choice would always have a similarly long payback time. I know of one eCommerce retailer that adopted a single vendor solution across its entire supply chain that took over eight years to show an ROI.

These large “scary” decisions are often driven by correspondingly longwinded and expensive selection processes. Such processes are clearly a major blocker for tech adoption becoming BAU due to their cost and duration. In the case of the above eCommerce solution, the procurement stage ended up taking over 12 months.

Making smaller decisions on a more regular basis lets us respond faster to technology change and external forces, and allows us to limit the time and money spent on procurement. We also need a faster time to ROI given the potentially short “shelf life”; a lower initial spend makes this more achievable.

2. Fail quickly and cheaply

If we make smaller investments, the implications of getting them wrong will be correspondingly limited. Conversely, many large technology transformations and/or adoptions end up in the “too big to fail” category, where the organisation as a whole is put at risk. In the case of the above eCommerce platform the board described the re-platforming as “betting the company”(!).

There are also cultural changes needed, specifically around the attitude to failure. Small changes mean lower amounts at risk, so failing quickly becomes less expensive. Instead of risking the whole organisation, these “experiments” represent a chance to learn something new for relatively small investments.

Unfortunately, too many large organisations tend towards catching and punishing small failures (because they can) and ignoring larger failures since they’ve “bet the company” on them. These organisations have created an “emperor’s new clothes” culture around their large programmes, where everyone knows they will fail but no one dares to tell the leadership. Failure is always a possibility, and it’s much better to fail quickly and cheaply.

3. Implement diverse coordinated architectures

Designing solutions that value interoperability over standardisation gives us the capability to move quickly when disruptive technologies arrive, as incorporating them won’t require rewriting the whole system. However, this means being more tolerant of duplication in your service, which runs contrary to the “received wisdom” many enterprise architects apply.

Received wisdom isn’t correct here: we need to value interoperability over standardisation

One driver for very large technology decisions is the desire for an end-state with a standardised uniform architecture, one that uses shared components to solve similar problems across the entire estate.

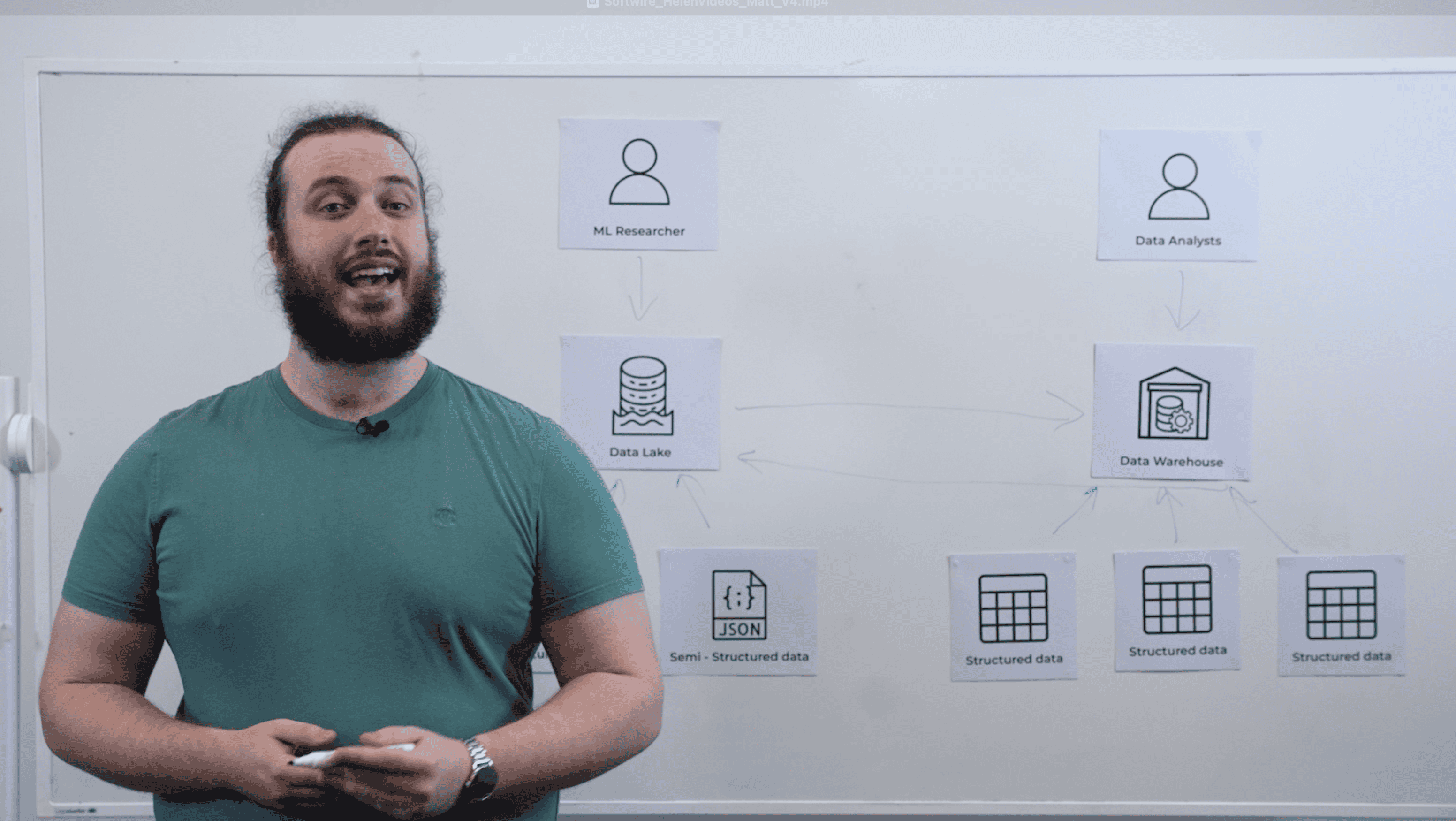

Data storage is a common example. For the eCommerce example I gave above, this approach resulted in single shared storage for almost everything, from stock levels through to customer details.

Normally there is an expectation this approach will reduce operational costs and remove duplication. This might be true on some levels, but this style of architecture can make small, fast decisions harder: Once we decide to create a single shared capability across the whole of the business it must necessarily encompass a broader range of requirements. There is a common feedback cycle here where the increasing complexity of large components pushes up cost, which in turn puts pressure on ROI, so we pull in yet more scope and requirements to create more benefits.

This is just one example of how a desire to make larger decisions — albeit one that is well motivated — can lead to a series of large investments with long payback periods. The push for standardisation and reuse can drive organisations into a way of working where small, fast and cheap decisions become much harder to achieve.

How can we move faster? Use interoperable components, and don’t be scared of duplication that supports useful agility

To move quickly we ideally need architectures composed of smaller components, which in turn need appropriate levels of interoperability and coordination. We also need to tolerate things that look like duplication from a technology point of view if this lets us move quickly in a way aligned to a particular business capability.

To give a concrete example, this can lead to federated styles of storage where components aligned with specific business capabilities store the information about, say, users, which is owned and used by that part of the business. We might still have some shared core user information and a common user identifier, but we have not created one single store for all possible user data.

We also need a shared understanding, along with the business, of how likely it is a component will need to change and what the limiting factors in that change might be. Sometimes the things that take the time are not technical at all, for example negotiating a contract with a new payment gateway provider.

Having an architecture comprised of smaller self-contained components clearly makes replacing any one thing smaller, cheaper and faster.

For many readers this will sound familiar: the microservices approach, which is one good example of a component-based architecture, although it’s not always implemented in a technically diverse way.

Moreover, effective architectural change needs to be driven both bottom-up from the teams and top-down by leadership.

Technology disruption resilience is business resilience

Organisations must become more resilient to technology disruptions. Moving to a technology strategy that embraces constant change and that makes technology adoption BAU is one possible approach. This will allow smaller, faster, lower-risk decision making, but might require a change to the underlying approach to architecture.

GenAI is just the latest and most visible example of technology disruptions to business. It will not be the last and the pace of change is going to increase. Organisations need to find a way to adapt, so responding to these disruptions becomes easier, more repeatable and less reactive.